Intro

Ok, I know that’s a long and pompous title, but it’s difficult to summarize the whole meaning of this post.

As you’ll find out on this blog I won’t only write about stupid projects, but I’ll write also posts about other things that I find interesting mainly on the embedded world.

When dealing with embedded Linux there are several things that need to be considered, because embedded usually refers to a vast ARM ecosystem that extends from the tiny cortex-M0 processor (ARMv6-M) to a cortex-A73 (ARMv8-A). Of course, you won’t see Linux on a cortex-M0 cpu but you may see it on a Cortex-M4.

There are two reasons for this post. The first one is to write some thoughts about when is preferred to use bare-metal, RTOS or Linux on embedded products. The second reason was this video, which leads to the question that after we’ve decided that we need to use Linux, then what options and tools do we have; and most importantly what happens with the code and binaries size? Well, in embedded you should care about size, because that can limit your options and also can affect your product cost, development time and budget.

Right now embedded is a hot topic and there a many things going on with the compilers, their optimizations and the system libraries. So what’s the deal with the compilers?

Compilers

On the embedded systems you can find many different compilers with fancy names, like arm-none-eabi-, arm-linux-gnueabi, gcc-arm-embedded and the list goes on. Assuming a specific architecture (e.g. ARM in this case), these compilers are all different but they all can be used to compile an application that doesn’t run on an OS. One of the main differences is that these compilers assume a different C library; therefore, arm-none-eabi assumes no C library or newlib and the arm-linux-gnueabi assumes the full blown glibc (or eglibc). So that means that usually if you cross-compile a bare metal source code for ARM (e.g. for an STM32 micro-controller) you should use arm-none-eabi- and when you cross-compile a Linux kernel or a Linux user space application you’ll use the arm-linux-gnueabi.

OS or RTOS?

This is another question that usually comes on the table when dealing with a new project. Usually, is pretty much clear if you need an OS or not, but the line between if you need Linux or another embedded RTOS (eRTOS) some times is blur. If you go with an eRTOS then you go with arm-none-eabi for the whole project, but if you go with Linux then you’ll need arm-none-linux-gnueabi.

The difference between eRTOS and Linux is huge. It’s much more complex to develop on an eRTOS compare to Linux, because in the eRTOS most of the times you’ll need to implement your own subsystems and underlying tasks that usually the Linux already provides. Also the Linux separated the kernel from the user space applications, but on a eRTOS the separation is not always achievable and you need to write in several different places in the eRTOS. On the other hand Linux takes care of all the low level mumbo jumbo and you only have to write your app using the kernel API. So what are the criteria that you decide which to choose? Well, that depends for many variables, like your existing code base, the development time, the platform tools, cost e.t.c. but now more than ever you need to consider also the size.

Size!

There’s no doubt that the size when using an embedded RTOS (eRTOS) will be much smaller but also comes with higher complexity; and some times is also difficult to chose the right eRTOS that will have the least problems, bugs and issues. In some cases where the cost of a small external RAM and eMMC/SD is not that high and the development comes with less complexity and faster development time, then you need to consider Linux. And this is what this post is all about.

Is it possible to shrink a Linux OS to a low cost embedded platform?

If the cost to use plenty of RAM and a big fast storage is not an issue, then Linux it’s a no brainer, but when there’s a cost restriction and at the same time there’s a budget to use a small ram and a cheap storage, then you must do a research if the current tools we have these days can deliver small enough user space code size.

How to shrink size?

The time this post is written there are a few tools that targeting to achieve small binary sizes. First, gcc already has some optimization flags that can be used to optimize speed and/or size. Also gcc provides a Link Time Optimization (LTO) tool (-flto flag in gcc), which also can reduce the compiled size. What LTO does, is that it gathers more details about the code during the compile time and then provides the linker with these details so the linker can use them to optimize further.

Apart from gcc there’s also the clang compiler which is designed to fully replace gcc. Therefore, when you build a source with clang then you don’t use gcc at all. Although clang is highly compatible with gcc, it doesn’t offer full compatibility, which means that you may not be able to compile all the existing code base.

In addition with the compilers, we also have the system libraries which also play significant role in the resulted binary size. GLib is the low level system library used by gcc and it’s huge! You would never consider the system library size when developing desktop applications, but for small embedded systems GLib is a behemoth. There are various light-weight replacement GLib libraries for the arm-none-linux-eabi, like the musl lib. You can see a comparison of few libraries here. Note, that there are also replacement glib libraries for the arm-none-eabi, like the nano-lib (specs=nano.specs compiler option)., which does a great difference in code size, too.

So, to sum up, we have different optimization flags, compilers and system libraries. Now, we can proceed with the benchmarks by using all these different options and see what happens.

Benchmarks

I’ve prepared a benchmark repository in bitbucket that you can you use to do your own benchmarks here:

https://bitbucket.org/dimtass/gcc_musl_clang_benchmark

You can git clone the repo and then run the benchmark.sh script followed with the c file and any extra flags you want, like this:

1

./benchmark.sh oggenc.c -lm

By default the binaries are created in the output/ folder and when the test is finished they are deleted; therefore, if you want to keep the binaries to do some tests then run the benchmark like this:

1

KEEP=true ./benchmark.sh oggenc.c -lm

I’ve included these 4 source code files: test.c, bzip2.c, gcc.c, oggenc.c. The test.c is a simple code file I’ve made and the rest files I’ve found them here. Every file has different size and source code and by comparing these we can obtain an overview of how well each benchmark performs in real applications.

These are the details for the compilers and libraries on my Linux Mint 18 `Sarah’ 64-bit.

GCC version: gcc (Ubuntu 5.4.0-6ubuntu1~16.04.4) 5.4.0 20160609GLib version: (Ubuntu GLIBC 2.23-0ubuntu7) 2.23clang version: clang version 3.8.0-2ubuntu4 (tags/RELEASE_380/final)musl version: 1.1.16`

And these are the results for each source file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

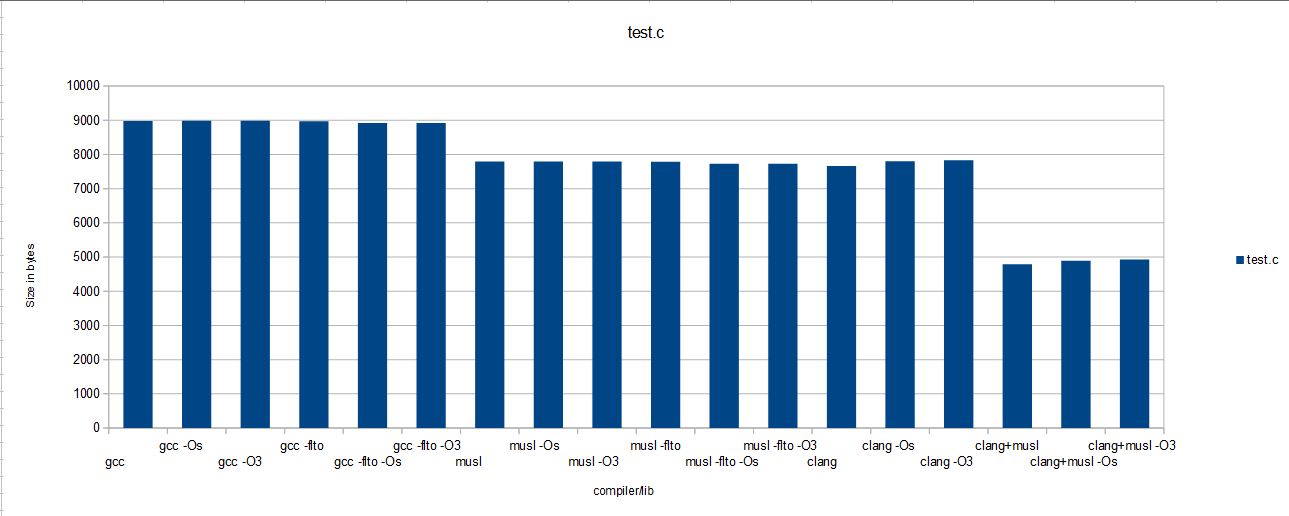

./benchmark.sh test.c

Testing file: test.c

gcc : 8976

gcc -Os : 8984

gcc -O3 : 8984

gcc -flto : 8968

gcc -flto -Os : 8920

gcc -flto -O3 : 8920

musl : 7792

musl -Os : 7792

musl -O3 : 7792

musl -flto : 7784

musl -flto -Os : 7728

musl -flto -O3 : 7728

clang : 7664

clang -Os : 7800

clang -O3 : 7832

clang+musl : 4792

clang+musl -Os : 4896

clang+musl -O3 : 4928

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

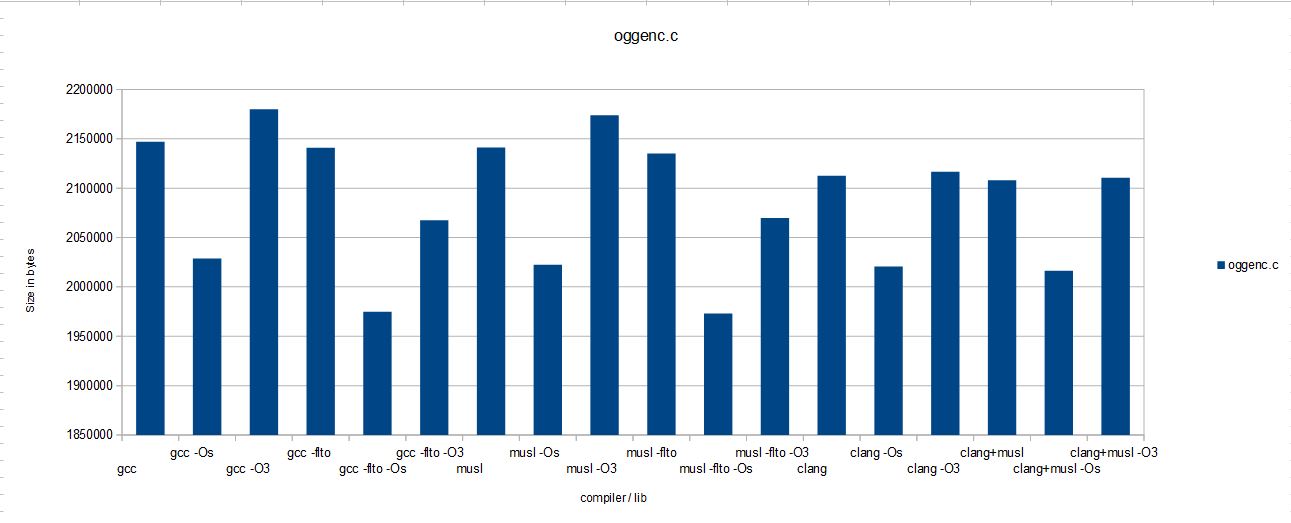

./benchmark.sh oggenc.c -lm

Testing file: oggenc.c -lm`

gcc : 2147072

gcc -Os : 2028656

gcc -O3 : 2179880

gcc -flto : 2140944

gcc -flto -Os : 1974736

gcc -flto -O3 : 2067600

musl : 2141096

musl -Os : 2022552

musl -O3 : 2173776

musl -flto : 2134952

musl -flto -Os : 1972976

musl -flto -O3 : 2069824

clang : 2112544

clang -Os : 2020600

clang -O3 : 2116544

clang+musl : 2107952

clang+musl -Os : 2016264

`clang+musl -O3 : 2110528

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

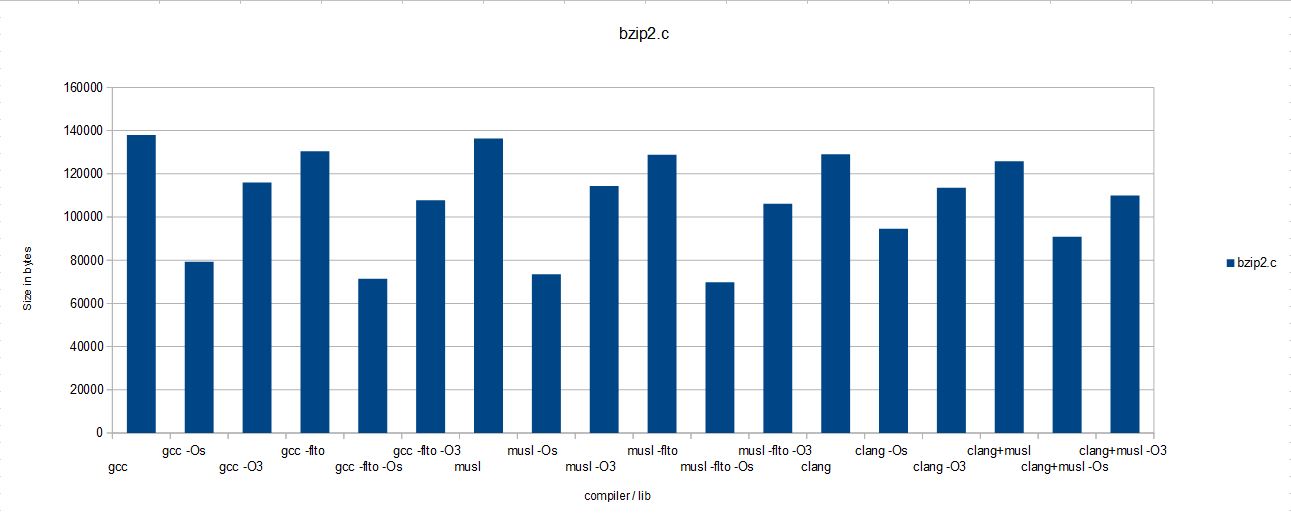

./benchmark.sh bzip2.c

Testing file: bzip2.c

gcc : 138008

gcc -Os : 79320

gcc -O3 : 115912

gcc -flto : 130448

gcc -flto -Os : 71456

gcc -flto -O3 : 107760

musl : 136376

musl -Os : 73512

musl -O3 : 114304

musl -flto : 128840

musl -flto -Os : 69728

musl -flto -O3 : 106152

clang : 129112

clang -Os : 94568

clang -O3 : 113504

clang+musl : 125840

clang+musl -Os : 90824

clang+musl -O3 : 109968

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

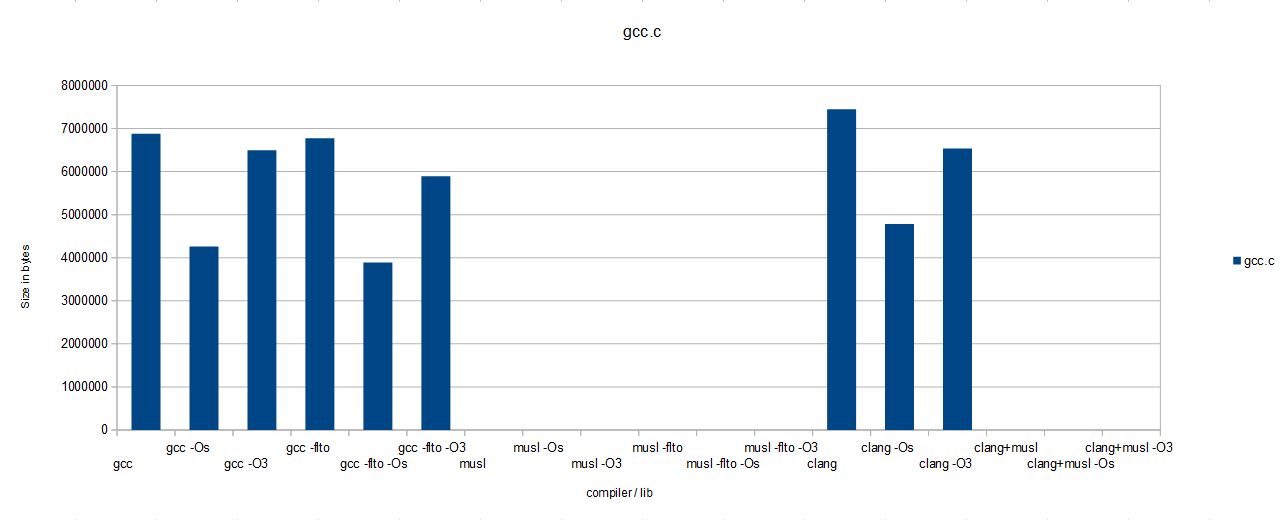

./benchmark.sh gcc.c

Testing file: gcc.c

gcc : 6879424

gcc -Os : 4263096

gcc -O3 : 6493624

gcc -flto : 6772760

gcc -flto -Os : 3886664

gcc -flto -O3 : 5889240

musl : failed

musl -Os : failed

musl -O3 : failed

musl -flto : failed

musl -flto -Os : failed

musl -flto -O3 : failed

clang : 7446328

clang -Os : 4785560

clang -O3 : 6537192

clang+musl : failed

clang+musl -Os : failed

clang+musl -O3 : failed

Analyzing the results

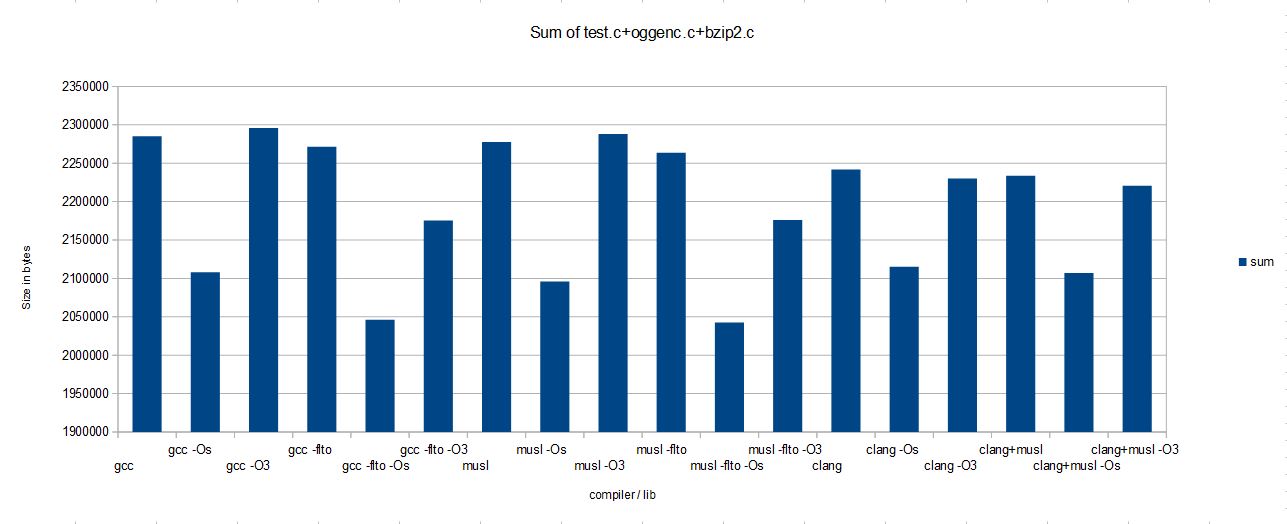

Now that we have the results we need to analyze them and the best way to do that is to visualize the data in a way that’s easy to compare the results. For that reason I chose to plot the size for each file against the compiler and the lib it was used and the last plot is the sum of all the output file sizes, except the gcc.c which was failed to build with the musl lib. Click on each image to zoom in.

Click to zoom images

Lets take this step by step. If you see the source code of the test.c you’ll find out that it’s a very simple program that doesn’t do much. There the combination of clang+musl shines and the result code is half the size compared to gcc+glib and also it is much smaller compared to gcc+musl. This is a very good sign for clang. Also clang by itself managed to produce almost the same binary size with gcc+musl. When I’ve seen these results I was surprised and I thought that this groundbreaking news and actually it is, but… after running the benchmarks with the rest of the files my feelings were mixed.

oggenc.cbenchmark shows that gcc+glib+LTO+Os and gcc+musl+LTO+O3 have the same performance and much smaller size compared to others benchmarks.bzip2.cshows that gcc+glib+LTO+Os, gcc+musl+Os and gcc+musl+LTO+Os perform the same and better that the rest.gcc.cfailed on musl and the gcc+glib+flto+Os performed better than the others.

Finally, the most important result is by adding the sizes of all the resulted builds as this is closer to real-life application as your rootfs size will be the sum of all the programs. Of course, only 3 programs doesn’t really reflect to let’s say 100 or 1000 or 2000 programs that your rootfs may really have, but still it’s a good measure to get a rough view of what it might be. By seeing the sum of the sizes is obvious that gcc+glib+LTO+Os and gcc+musl+LTO+Os perform much better that the others and clang is far behind.

You can make your own conclusions with the result and even better try by your self.

Conclusion

From the things I’ve seen my opinion is that the LTO combined with the -Os does the most significant difference compared the other options. That means that the gcc compiler optimizations outperform clang and also it seems that musl doesn’t give much more compared to glib. Of course the last statement isn’t always true. Musl does make a huge difference on some programs (test.c) and it doesn’t make on others (oggenc and bzip), but also it failed to build gcc. I think musl looks promising though. On the other hand clang results were very mixed. On a simple application test.c it produces really small binary and outperforms all the other options but when the things get tough in more complex code, is worse that gcc.

So, let’s go back to the first question. Does it worth? Can these results help us to get a decision on the thin line between choosing an RTOS and a Linux OS for an embedded product? Well, don’t expect this answer from me. You are the one to decide what is right for you, but I’ll tell you what I would do.

Personally, I break the embedded projects needs in three categories like sequential execution, couple of parallel threads and real multi-thread.

- If your project can be implemented with sequential execution procedures you don’t need RTOS or Linux, you go with bare metal.

- If you project needs 1 or 2 threads, then that doesn’t mean that you need an RTOS. You can develop using finite states (FSM); but if for some reason you think that your FSM will be hard to maintain (e.g. a complex GUI with user inputs and peripherals) then go for an RTOS.

- If you have a couple of threads and the cost must be kept low then go for RTOS.

- If you have multiple threads and the budget allows you to add some RAM and a small storage go for Linux.

- If your code base is on Linux, then of course, you go for Linux.

In any case is good to use optimizations. Nano-lib for bare-metal and compiler optimizations & alternative system libraries for the OS.

Now, if you decide to go with Linux and a limited budget then you’ll need all the performance gains the compiler and the alternative system libraries can offer. In that case you need to verify that all the core programs you need in your rootfs can be compiled with all the above optimizations and the result size is small enough to meet your specs on RAM and storage.

It’s encouraging to know that there’s an active development and effort to the correct path. Size matters and it can do the difference and introduce Linux in the low budget projects. Of course, Linux is not a panacea for every embedded project and it shouldn’t be, but it has it’s use and it can solve problems.

Also, many cheap linux-enabled SBCs are showing up these days. For example have a look at Omega2, which is a $5 SBC with Linux, 64MB memory, 16MB storage, USB, WiFi, I2C, SPI, i2S and 15 GPIOs. On the other side a cheap stm32f103c8t6 board (Cortex-M3) costs $2.5 and an stm32f407vet6 board costs $7. NXP ARM mcus are much more expensive as also Renesas, Cypress and others. Of course, the STM boards have more peripherals and still they have their use, but the future for the most mainstream products seems to be the ultra low cost Linux IOT ready boards and for that reason we need smaller size binaries and better performing compilers and tools.

For those that only develop only on small ARM mcus, don’t worry! There are many reasons that low embedded will be still on the market in the next years, no matter what happens. Especially on industries that have to do with health, human life, security, defense e.t.c. where everything needs to be absolutely deterministic. An RTOS or any other OS is non-deterministic and regardless the budget and the costs they can’t be used on these products as the regulations and approvals are very strict about this.

Have fun!

Comments powered by Disqus.